Isolation was a long American tradition. Since the days of George Washington, Americans struggled to remain protected by the mighty oceans on its border. When European conflicts erupted, as they frequently did, many in the United States claimed exceptionalism. America was different. Why get involved in Europe’s self-destruction?

When the Archduke of Austria-Hungary was killed in cold blood, igniting the most destructive war in human history, the initial reaction in the United States was the expected will for neutrality.

As a nation of immigrants, The United States would have difficulty picking a side. Despite the obvious ties to Britain based on history and language, there were many United States citizens who claimed Germany and Austria-Hungary as their parent lands. Support of either the Allies or the Central Powers might prove divisive.

In the early days of the war, as Britain and France struggled against Germany, American leaders decided it was in the national interest to continue trade with all sides as before. A neutral nation cannot impose an embargo on one side and continue trade with the other and retain its neutral status.

In addition, United States merchants and manufacturers feared that a boycott would cripple the American economy. Great Britain, with its powerful navy, had different ideas.

Original caption: One of the signs of America’s entry into the war, in Cincinnati, Ohio. Notice of mail suspension with Central Powers, posted in the main post office, April 15, 1917.

A major part of the British strategy was to impose a blockade on Germany. American trade with the Central Powers simply could not be permitted. The results of the blockade were astonishing.

Trade with England and France more than tripled between 1914 and 1916, while trade with Germany was cut by over ninety percent. It was this situation that prompted submarine warfare by the Germans against Americans at sea.

On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson went before a joint session of Congress to request a declaration of war against Germany. Wilson cited Germany’s violation of its pledge to suspend unrestricted submarine warfare in the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean, as well as its attempts to entice Mexico into an alliance against the United States, as his reasons for declaring war.

On April 4, 1917, the U.S. Senate voted in support of the measure to declare war on Germany. The House concurred two days later. The United States later declared war on German ally Austria-Hungary on December 7, 1917.

Original caption: American-built tank “America”, designed by Professor E.F. Miller of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Photographed in July of 1918.

The first and most important mobilization decision was the size of the army. When the United States entered the war, the army stood at 200,000, hardly enough to have a decisive impact in Europe. However, on May 18, 1917, a draft was imposed and the numbers were increased rapidly.

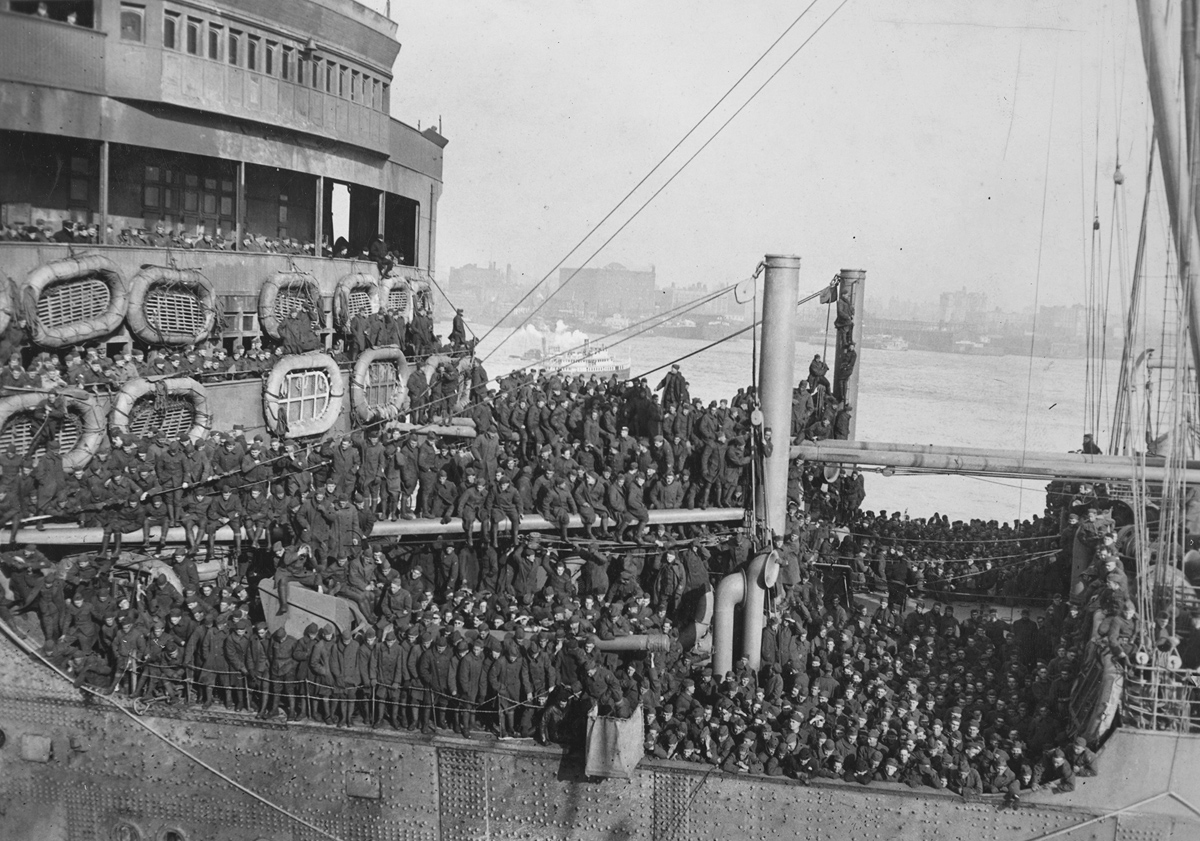

Initially, the expectation was that the United States would mobilize an army of one million. The number, however, would go much higher. Overall some 4,791,172 Americans would serve in World War I. Some 2,084,000 would reach France, and 1,390,000 would see active combat.

The first military measures adopted by the United States were on the seas. Joint Anglo-American operations were highly successful at stopping the dreaded submarine.

Following the thinking that there is greater strength in numbers, the U.S. and Britain developed an elaborate convoy system to protect vulnerable ships.

In addition, mines were placed in many areas formerly dominated by German U-boats. The campaign was so effective that not a single American soldier was lost on the high seas in transit to the Western front.

Men sit astride their Harley-Davidson motorcycles, part of the New York National Guard’s Motorcycle Division, circa 1917.

The American Expeditionary Force began arriving in France in June 1917, but the original numbers were quite small. Time was necessary to inflate the ranks of the United States Army and to provide at least a rudimentary training program. The timing was critical.

When the Bolsheviks took over Russia in 1917 in a domestic revolution, Germany signed a peace treaty with the new government. The Germans could now afford to transfer many of their soldiers fighting in the East to the deadlocked Western front. Were it not for the fresh supply of incoming American troops, the war might have followed a very different path.

The new soldiers began arriving in great numbers in early 1918. The “doughboys”, as they were labeled by the French were green indeed. Many fell prey to the trappings of Paris nightlife while awaiting transfer to the front.

An estimated fifteen percent of American troops in France contracted venereal disease from Parisian prostitutes, costing millions of dollars in treatment.

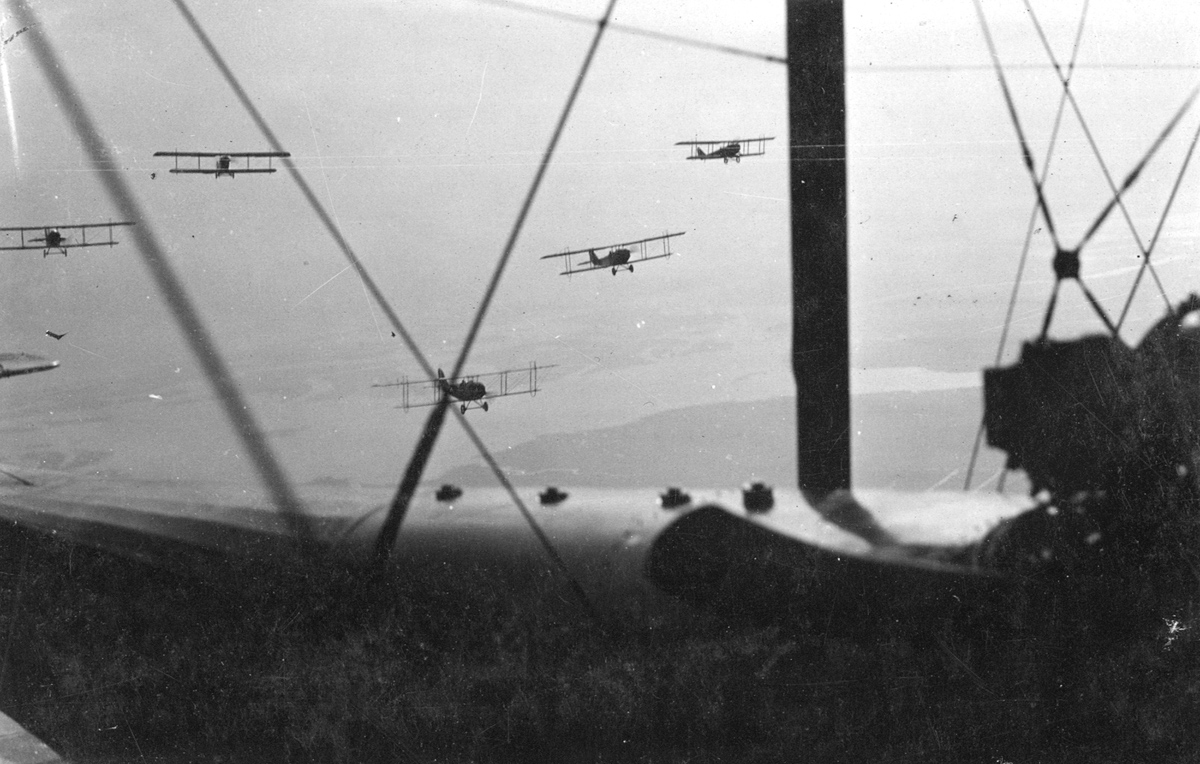

A squadron of U.S. Curtis aircraft in flight, circa 1917.

The African American soldiers noted that their treatment by the French soldiers was better than their treatment by their white counterparts in the American army. Although the German army dropped tempting leaflets on the African American troops promising a less-racist society if the Germans would win, none took the offer seriously.

By the spring of 1918, the doughboys were seeing fast and furious action. A German offensive came within fifty miles of Paris, and American soldiers played a critical role in turning the tide at Chateu-Thierry and Belleau Wood.

In September 1918, efforts were concentrated on dislodging German troops from the Meuse River. Finding success, the Allies chased the Germans into the trench-laden Argonne Forest, where America suffered heavy casualties.

But the will and resources of the German resistance were shattered. The army retreated and on November 11, 1918, the German government agreed to an armistice. The war was over. Over 14 million soldiers and civilians perished in the so-called GREAT WAR.

For the United States, the human and economic costs of the war were substantial. The death rate was high: 48,909 members of the armed forces died in battle, and 63,523 died from disease.

Many of those who died from disease, perhaps 40,000, died from pneumonia during the influenza-pneumonia epidemic that hit at the end of the war. Some 230,074 members of the armed forces suffered nonmortal wounds.

John Maurice Clark provided what is still the most detailed and thoughtful estimate of the cost of the war; a total amount of about $32 billion. Clark tried to estimate what an economist would call the resource cost of the war.

For that reason, he included actual federal government spending on the Army and Navy, the number of foreign obligations, and the difference between what government employees could earn in the private sector and what they actually earned.

He excluded interest on the national debt and part of the subsidies paid to the Railroad Administration because he thought they were transfers. His estimate of $32 billion amounted to about 46 percent of GNP in 1918.

Original caption: Brooklyn’s drafted men leaving Long Island R.R. terminal on Flatbush Avenue, for Camp Upton, in September of 1917.

American soldiers drilling at home. Original caption: Men in the trenches with gas masks on ready to go over the top. Presidio Barracks, San Francisco, California, in June of 1918.

Original caption: Running the welding machine. War time women workers in naval aircraft factory in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, circa 1918.

Testing tanks in the mud. Original caption: Mud hole in testing field at van Dorn Iron Works Company in Cleveland, Ohio.

Men run from an exploding balloon at Post Field, Fort Sill, Oklahoma, on April 2, 1918.

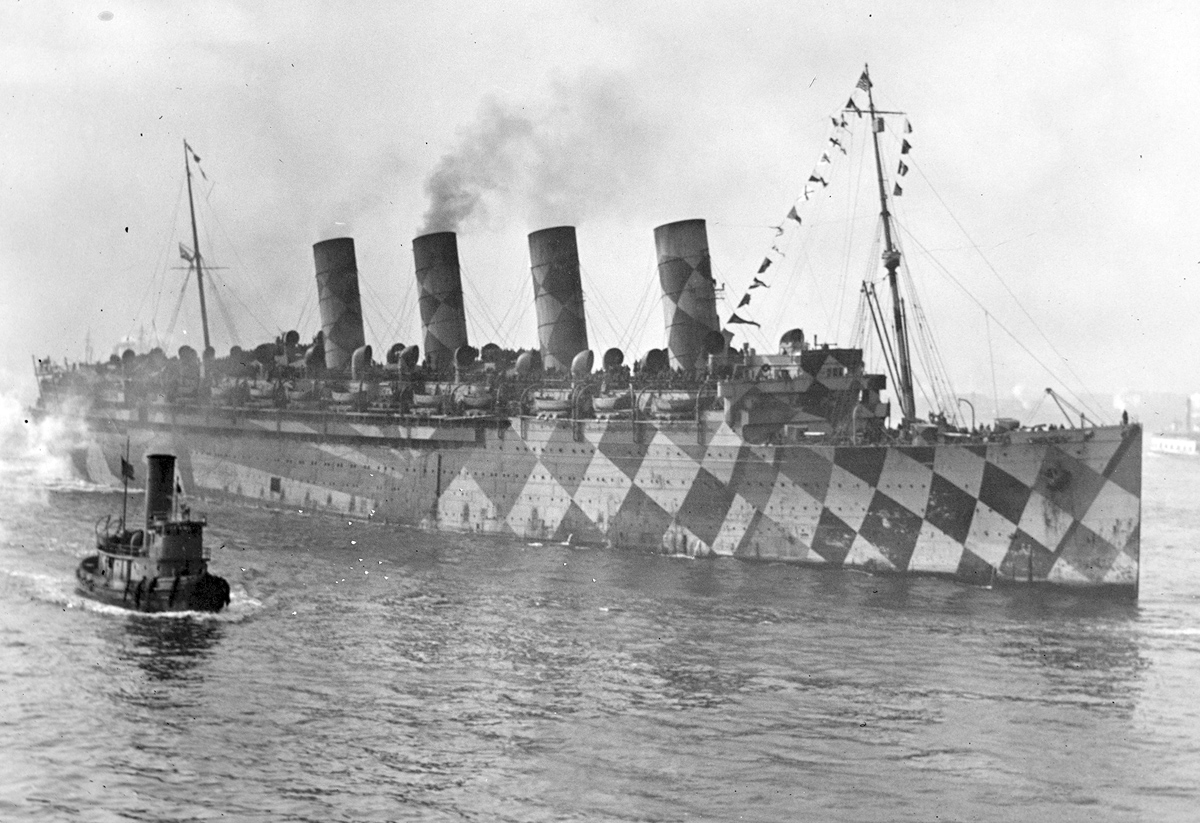

Experimenting with dazzle camouflage patterns. Original caption: Experiments on models of vessels to illustrate various methods of camouflage on different types of ships. Camouflage department, U.S. Navy, Washington, DC.

Once painted, the camouflaged ships would be placed on a tabletop to be viewed through a periscope, simulating conditions at sea, to evaluate the effectiveness of the patterns. Original caption: Models of two ships on same line of direction, one plain, and the other dazzled. This method of camouflage was used on battleships and transports to deceive U-Boat commanders and make correct aim difficult.

The RMS Mauretania in an American port with dazzle camouflage.

Original caption: Physical training twenty-two stories in the air. Men and girls employed by the New York State Industrial Commission going through physical exercises designed for the National Security League, on the roof of the Victoria Building in New York.

Original caption: Three motorcycle dispatch bearers in training at the U.S. Training Detachment School in Richmond, Virginia, wearing their gas masks, ready to start on a dispatch carrying trip in an exhibition.

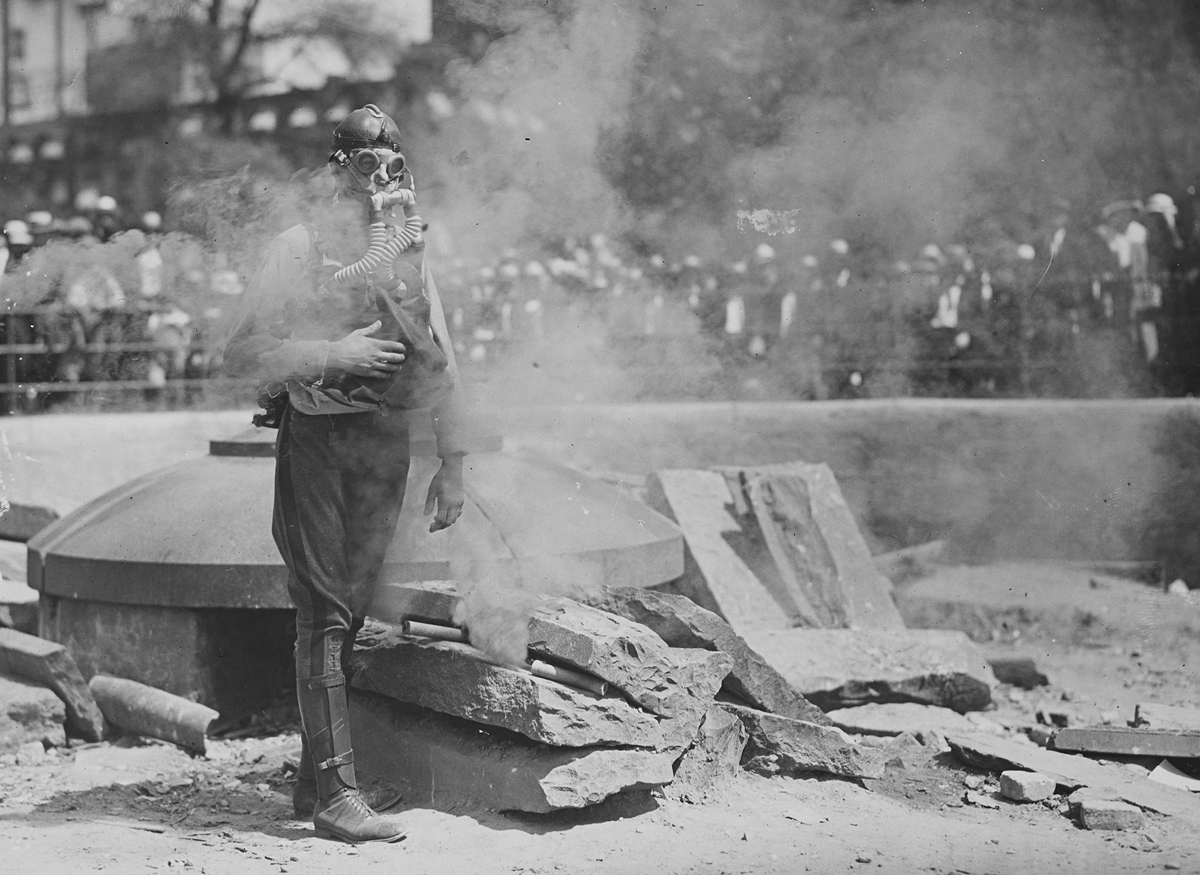

Original caption: A Boy Scout testing a gas mask in Union Square, New York City.

Original caption: Wives and mothers of men at the front, being instructed in shooting at the Wakefield rifle range in Wakefield, Massachusetts, by Major Portal and U.S. Marines.

American soldiers attend a Christmas Dinner in Camp Logan, in Texas.

Aircraft fly above New York City.

Original caption: Carrier pigeons are being trained for service with the armies abroad and here. A pigeon section of the Signal Corps has been established under the command of Major Griffith, and a flight was held in May of 1918, from Washington to New York. A flock of 3,500 birds made the trip.

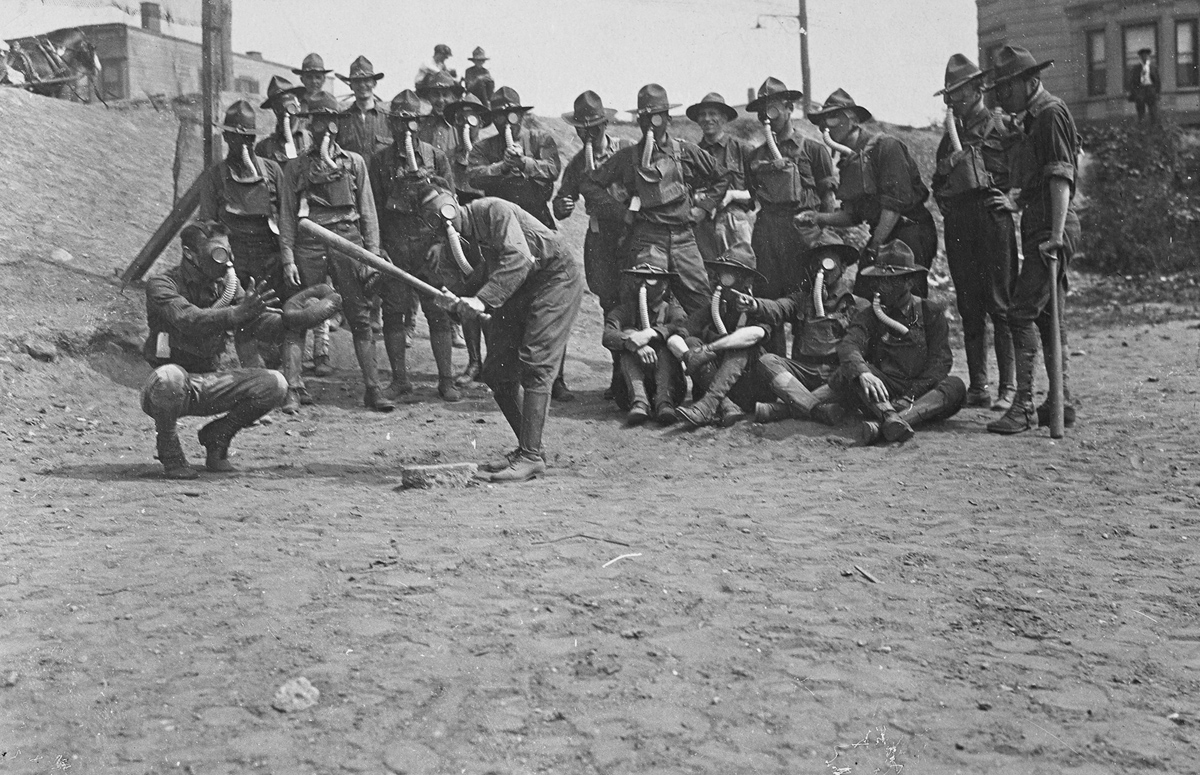

Soldiers playing baseball while wearing gas masks. Original caption: It is not troubling these soldiers any to play ball while wearing their gas masks. Gas Defense Plant, Long Island, New York.

Original caption: Mascot of the U.S.S. Pennsylvania, amusing some of the sailors.

Original caption: Advancing over No Man’s Land. Troops moving forward over ground that has been thoroughly churned up by shells from big guns, July, 1918.

French ruins. Original caption: Aerial view of Seicheprey, France.

Original caption: War horse being well cared for in the big conflict. The average life of a horse in the war zone is six weeks. Scene in a German veterinary hospital in the field. A horse, being wounded by shrapnel, is being made ready for an operation.

Original caption: Wrecked French chateau. Chateau destroyed by German shell fire, Dives, Oise, France.

Original caption: British tank going into action.

An aircraft flies over no-man’s land, a European battlefield torn up by bombs and trench diggers.

Original caption: Ike Sims of Atlanta, Georgia, 87 years old, has eleven sons in the service.

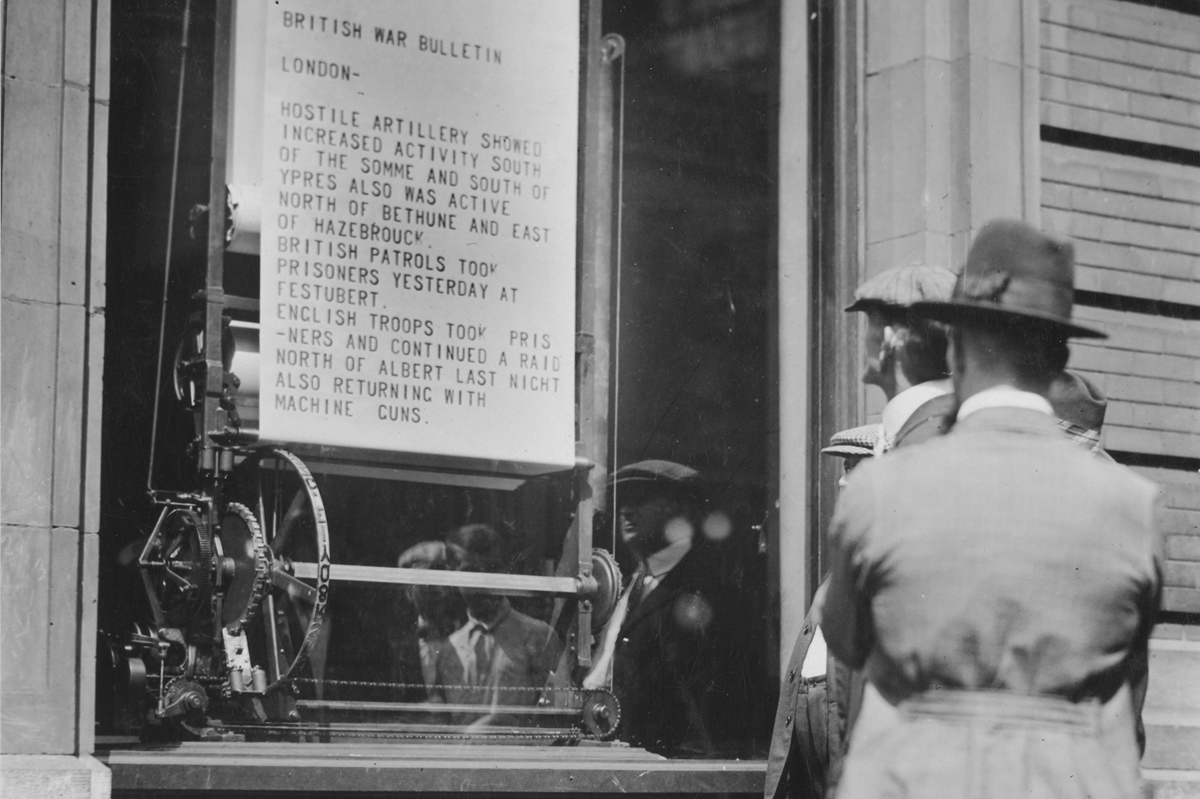

Original caption: War news printed right before your eyes is the latest method of displaying bulletins by big newspapers. The mechanical bulletin printing machines in the window of a Cincinnati newspaper. It is a linotype machine and a printing press combined.

Original caption: Crater caused by an American bomb. Taken at Langley Field, showing the wide crater made by a certain type of bomb released from an aeroplane.

A wounded man recovers in a hospital bed.

Masks made for men with disfigured faces from war wounds. Original caption: Mrs. Ladd coloring one of the masks after adjusting on a wounded Poilu’s face. Read more about Mrs. Ladd work with the disfigured veterans of the Great War.

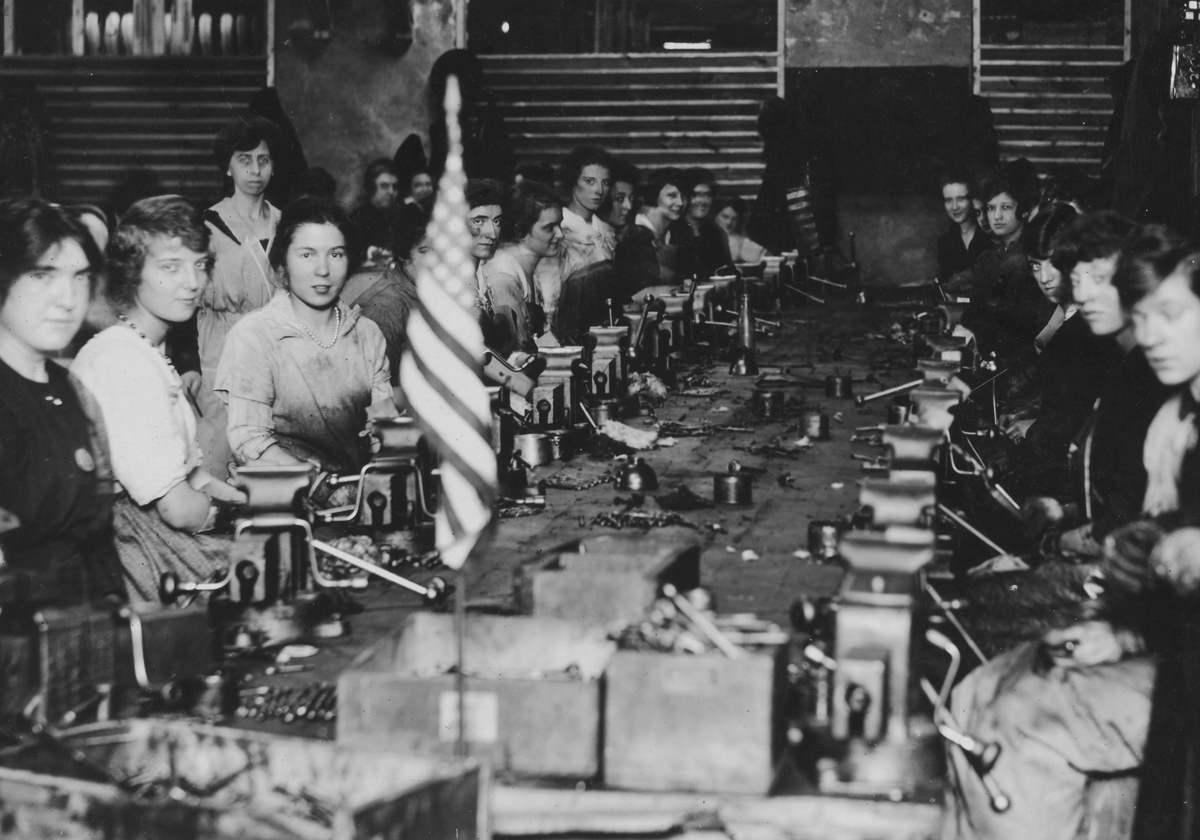

Original caption: Turnbuckle girls, Standard Aircraft Corp., Plainfield, New Jersey.

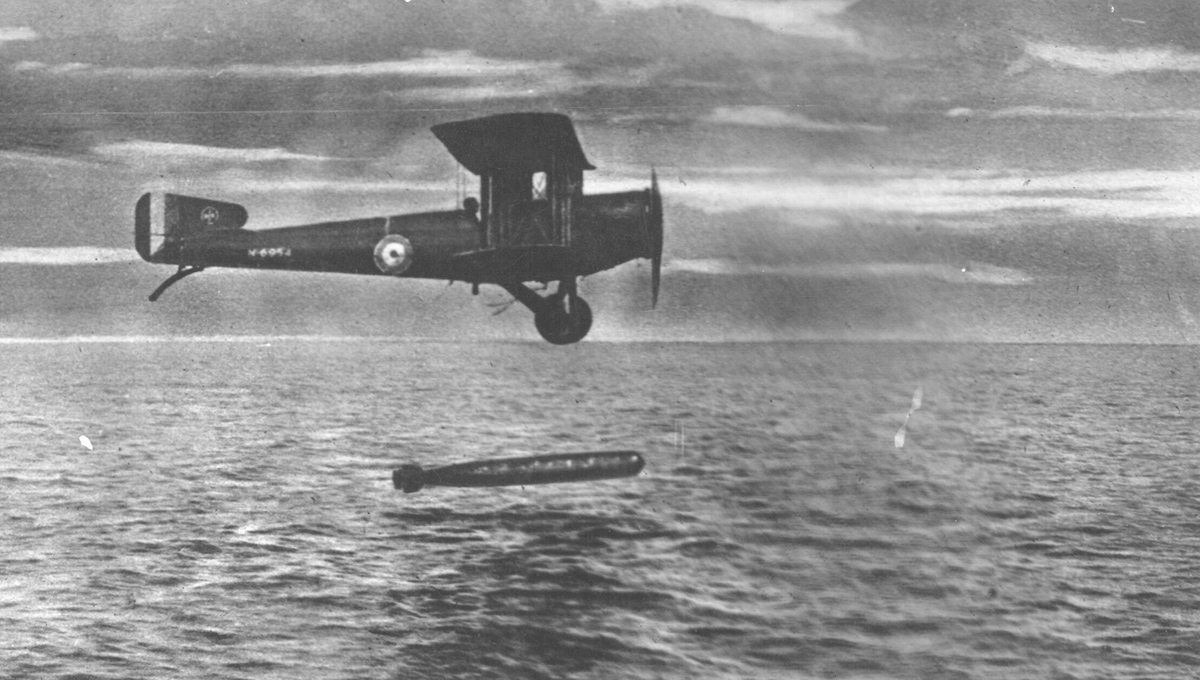

Sea launch. Original caption: Aeroplane leaving a light cruiser.

Original caption: Some of the colored men of the 369th (15th, NY) who won the Croix de Guerre for gallantry in action. Front row, left-to-right: Private Eagle Eye, Ed Williams; Lamp Light, Herbert Taylor; Private Leon Fraitor; Private Kid Hawk, Ralph Hawkins. Back row, left-to-right: Sgt. H.D. Prinas; Sgt. Dan Storms, Private Kid Woney, Joe Williams; Private “Kid Buck”, Alfred Hanley; and Corporal T.W. Taylor.

Original caption: Parade of returned fighters of the famous 369th colored Infantry at the Flatiron building in New York City.

British fleet in the Firth of Forth. Original caption: taken from a rigid balloon showing the English fleet in the Firth of Forth where the German fleet was turned over to the allies.

Original caption: The torpedo-aeroplane, a new arm precluded by armistice. Among new devices which armistice prevented Royal Air Force from putting into use against enemy was the torpedo-aeroplane.

Original caption: The Leviathan that brought back 166th Infantry. The Leviathan returned with 12,000 of our boys from France. Among them were the 166th Infantry, 42, Rainbow Division

(Photo credit: U.S. National Archives )