Their lives took a dramatic turn when they were plucked from a Virginia farm and thrust into the bright lights of the circus world. Their story is one of uniqueness, exploitation, and, ultimately, liberation.

George and Willie Muse, the eldest of five siblings, were born to Harriett Muse in the small community of Truevine on the outskirts of Roanoke, Virginia.

Born with albinism, a genetic condition that bestowed upon them pale skin, white hair, and striking blue eyes, they possessed features that set them apart from their peers.

In addition to albinism, both boys also had nystagmus, a common occurrence with albinism that affected their vision.

Their struggles with light sensitivity began so early that by the ages of six and nine, they already had permanent furrows etched into their foreheads.

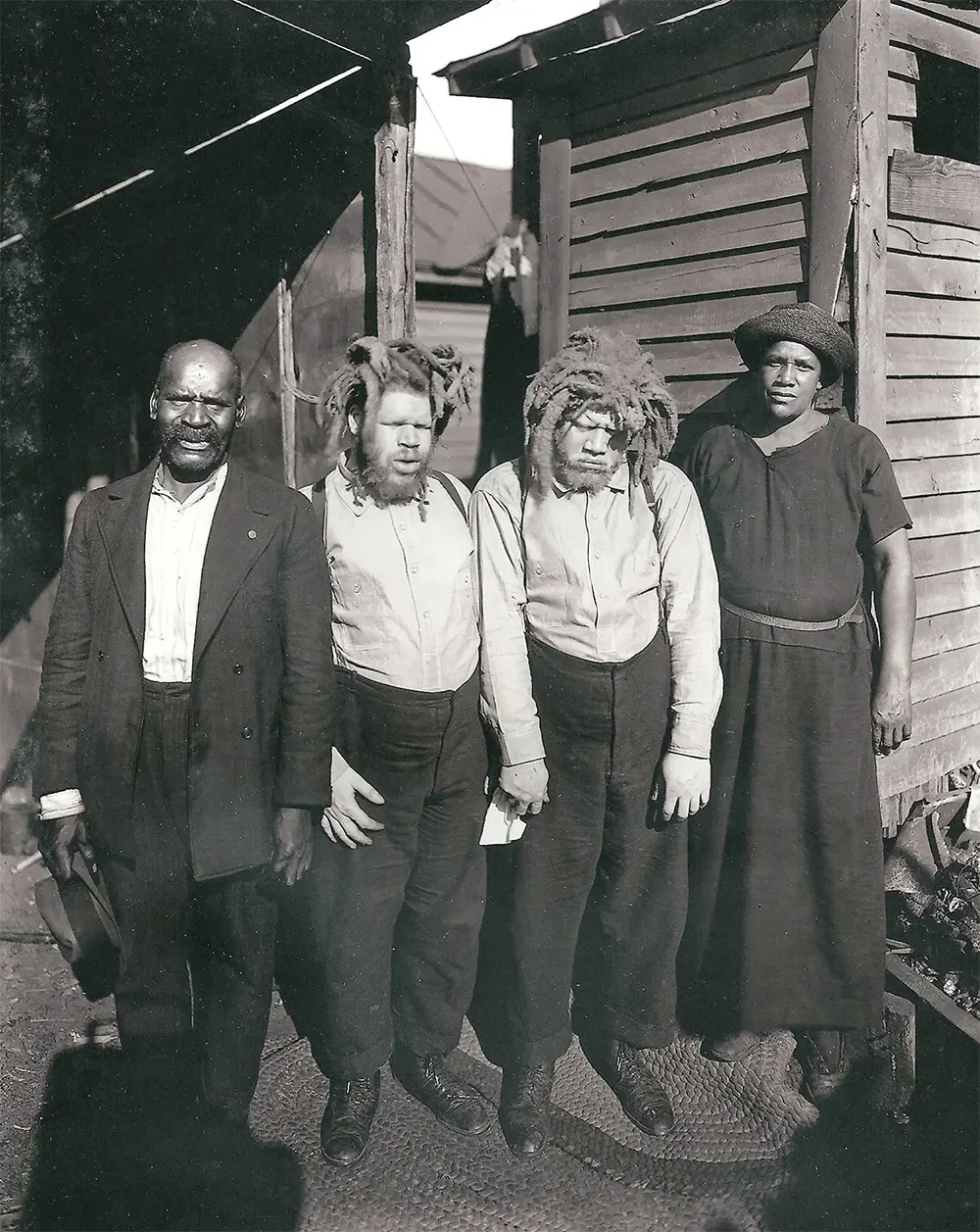

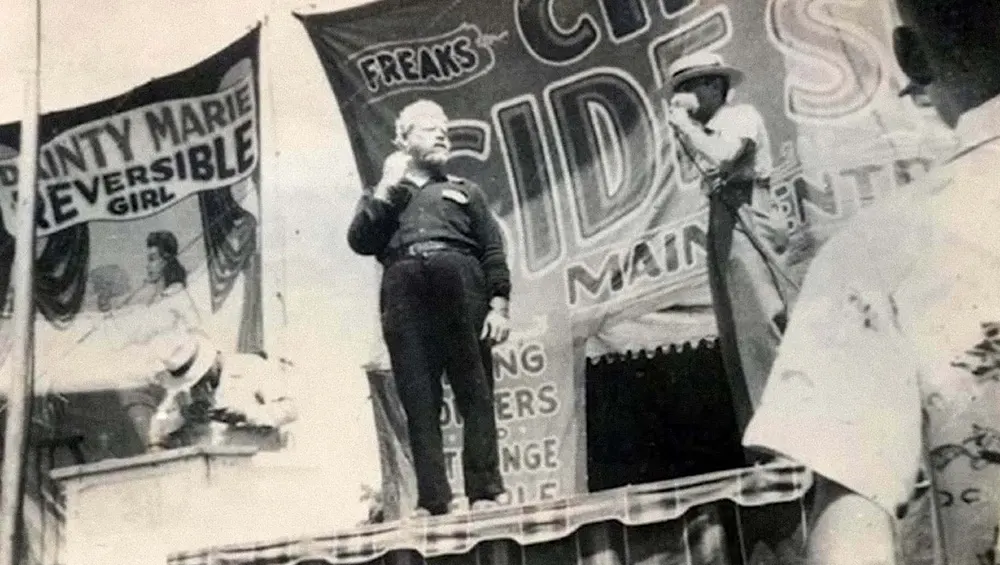

The Muse brothers: Willie (left) and George with showman Al G Barnes, 1918-22. (Photograph courtesy of Josh Meltzer).

Much like their neighbors, the Muse family relied on sharecropping tobacco for their livelihood.

The boys were expected to contribute by protecting the tobacco plants from pests, a task that involved eradicating potential threats before they could harm the precious crop.

Although Harriett Muse cared for her sons as best as she could, their life was characterized by grueling manual labor and the looming threat of racial violence.

Being Black children with albinism made the Muse brothers even more vulnerable to discrimination and mistreatment.

In 1899, six-year-old George and his nine-year-old brother Willie came to the attention of a “freak hunter” named James Herman “Candy” Shelton.

Shelton was searching for sideshow attractions that could match the popularity of renowned acts like the conjoined twins from Thailand, known as Chang and Eng, or the dwarf brothers from Ohio, famously labeled the Wild Men of Borneo by circus showman PT Barnum.

A 1924 “class photograph” of sideshow acts in the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus. George Muse is third from left, upper row; Willie is third from right. (Photo by the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art Tibbals Collection).

According to Beth Macy, the author of “Truevine,” it is suggested that the Muse family initially agreed to let the albino brothers participate in a few performances with Shelton’s circus when it visited Truevine in 1914.

However, it is alleged that Shelton took a different path and abducted the brothers when his circus left town.

The popular story which sprang up in Truevine was that the brothers were out in the fields one day in 1899 when Shelton lured them with candy and kidnapped them.

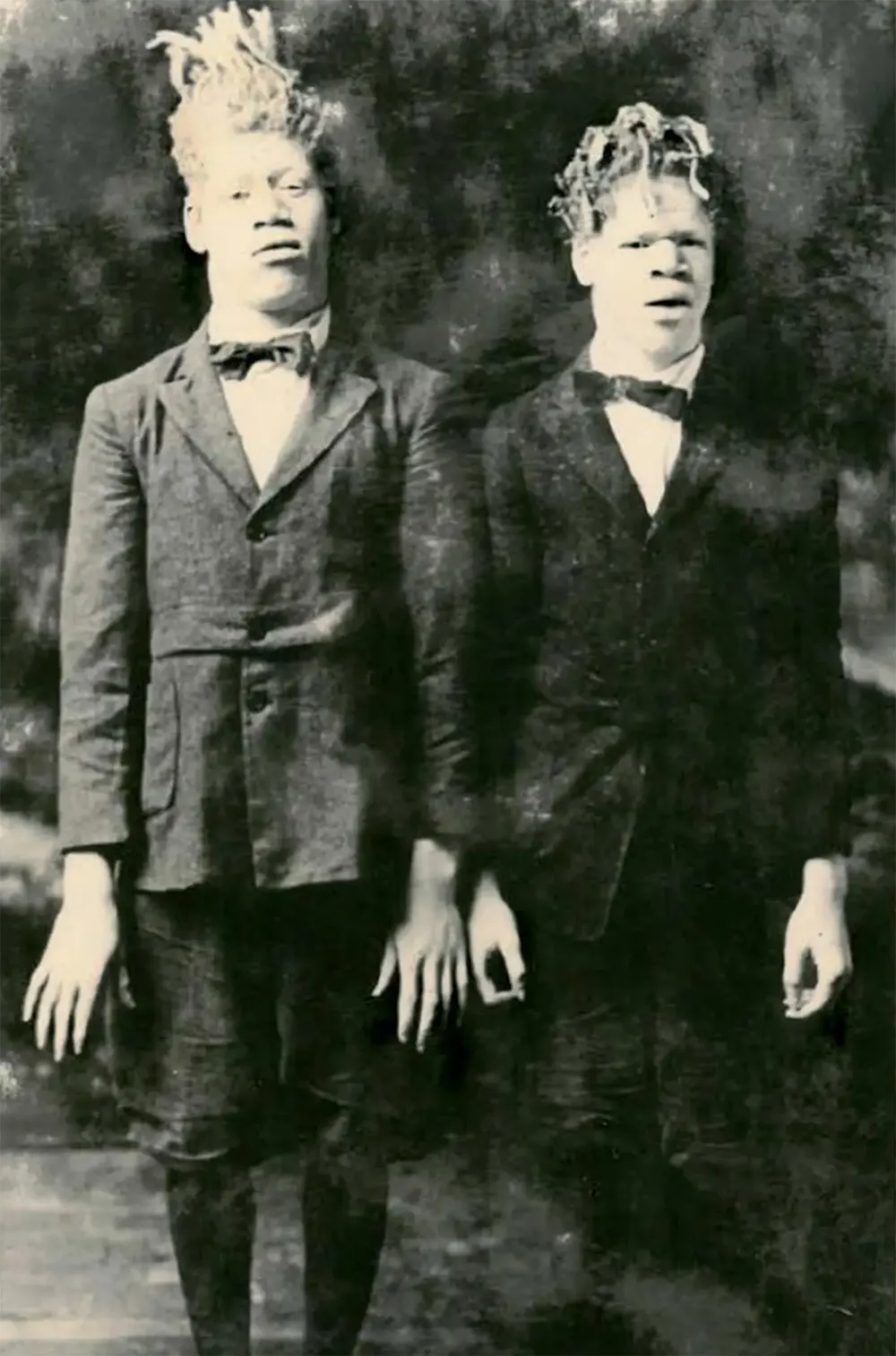

Eko and Iko in a promotional photo.

How Muse Brothers Became Part of Freakshows

During the early 20th century, the circus held a significant role as a form of entertainment across America.

Alongside the main circus acts, sideshows featuring “freak shows” and demonstrations of unique talents, like sword swallowing, sprang up along roadsides throughout the nation.

In this era, Candy Shelton recognized an opportunity. At a time when disabilities were often exploited for public curiosity and Black individuals faced systemic discrimination, Shelton saw the potential for substantial profit in the young Muse brothers.

From their introduction to the circuit until 1917, the Muse brothers (now known as Eko and Iko) were under the management of Charles Eastman and Robert Stokes.

They were promoted under various names, including “Eastman’s Monkey Men,” the “Ethiopian Monkey Men,” and the “Ministers from Dahomey.”

In the early 20th century, circuses and traveling carnivals were a leading form of entertainment for people throughout the United States. Pictured: a show titled “Human Freaks”.

The Muse brothers didn’t get to go to school or learn to read during this time, and they weren’t paid for their work. They were even told their mother had died to stop them from wanting to go back home.

One day, a circus photographer gave them a banjo and a guitar and asked them to pose with these instruments for photos.

At first, their manager thought it was a joke because he didn’t believe the brothers could play any music.

But it turned out that George and Willie had a special talent – they could teach themselves to play almost any tune.

Even though George was just three years older, he became Willie’s protector and spoke for both of them. George did most of the talking, while Willie expressed himself mainly through music.

During World War I, they found comfort in a popular song called “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” a song about missing home.

George and Willie were displayed under an array of humiliating names, complete with absurd backgrounds tailored to lure audiences.

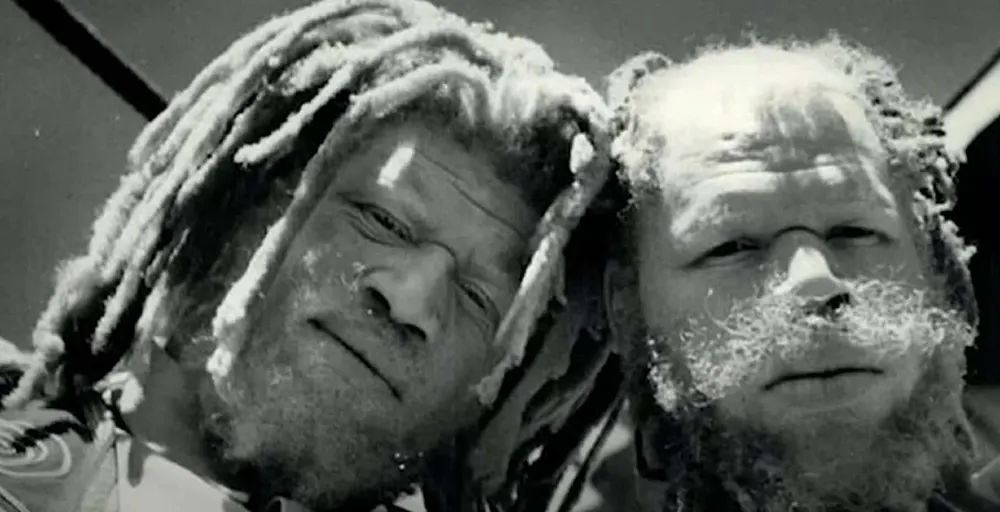

As years went by, the brothers underwent some dramatic changes in how they looked. They were dressed in flashy costumes, and their hair was styled into unique dreadlocks that looked like fireworks exploding from their heads.

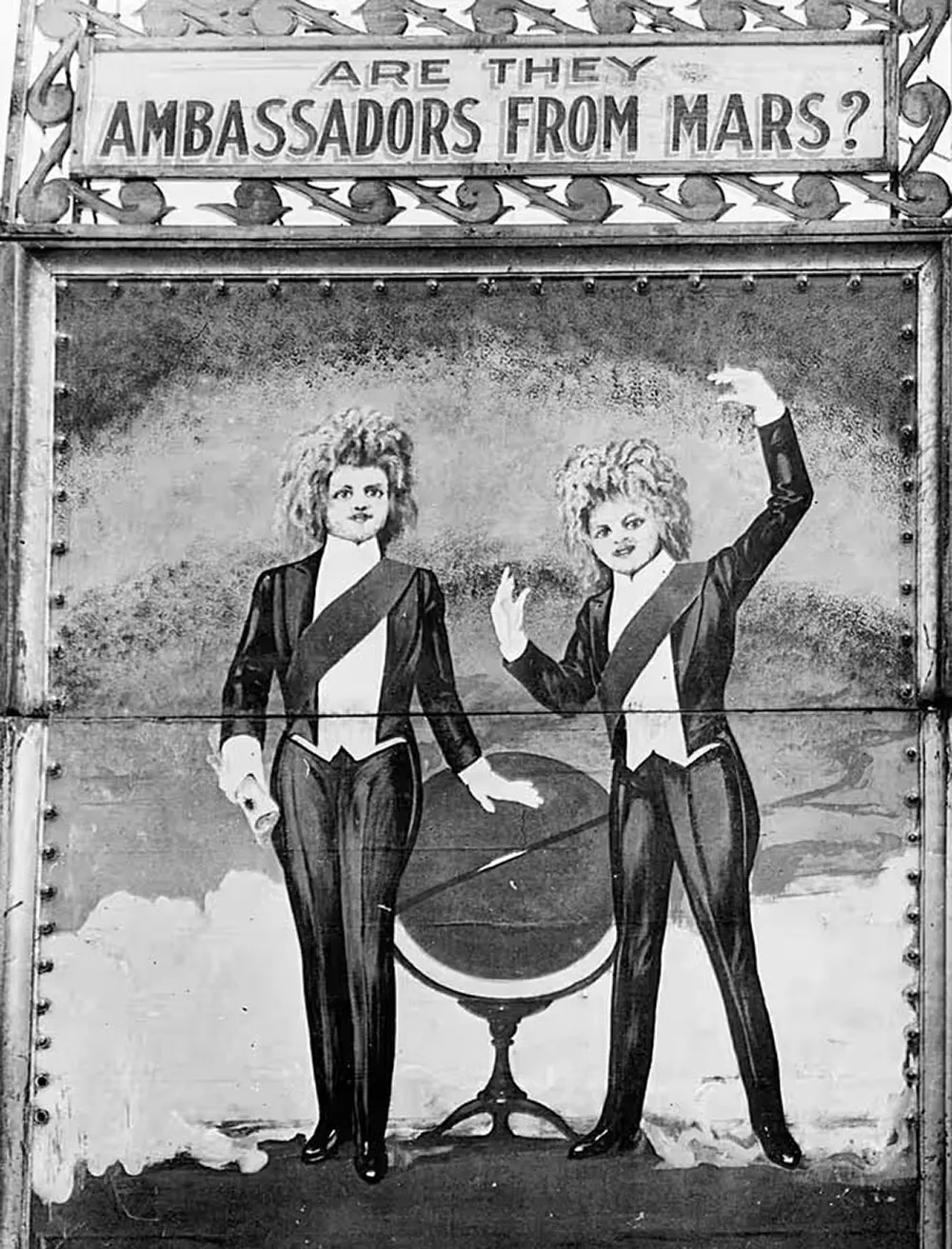

Big banners called them “the Ambassadors from Mars,” and “the Sheep-headed Men.”

Alongside these titles were imaginative stories about their origins, ranging from being found on a raft near Madagascar to discovering them in the Mojave Desert.

As showman Al G. Barnes recalled in his 1936 memoir: “There was a story to the effect that the boys were members of a colony of sheep-headed people inhabiting an island in the South Seas; that they had been captured after many hair-raising escapes, and that they were the only specimens in captivity. The boys had a very low grade of intelligence, and the press-agent story fitted them well.”

Eko and Iko with some of their coworkers at the circus.

The Muse Brothers Reunite with their Mother

In October 1927, when the circus rolled into Roanoke, the Muse brothers were being promoted as something even more extraordinary than Sheep-headed Men.

A banner outside the sideshow posed the intriguing question, “Are they ambassadors from Mars?”

According to the storyline, Eko and Iko had allegedly been discovered in 1923 emerging from a hole near the wreckage of a spacecraft in the Mojave Desert.

The idea of these supposed Martians playing popular tunes under a tent in Virginia might have seemed utterly nonsensical, but it didn’t dissuade the curious crowds from flocking to see them.

George and Willie Muse in the earliest known photograph of them in the circus. (Photo by John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art Tibbals Collection).

On that autumn day at the Roanoke fairgrounds, while George strummed the mandolin and Willie played the guitar, something remarkable caught their attention—a black woman had managed to make her way to the front of the predominantly white audience.

“There’s our dear old mother,” George exclaimed. “Look, Willie, she is not dead.”

They promptly set aside their instruments and rushed to embrace the woman they hadn’t seen in well over a decade.

During this period, Harriett Muse worked as a maid and laundress in Roanoke.

Despite her illiteracy, she had somehow learned that her sons were coming to town. Finally, after all these years, the brothers had reunited with their mother.

Harriett Muse, right, and husband Cabell, far left, with the brothers shortly after she found them at a sideshow in 1927. (Photo by George Davis).

The press took an interest in the Muse brothers’ story, and public sentiment overwhelmingly favored the mother’s quest for justice.

The case garnered widespread attention, revealing the egregious injustices that the brothers had endured for so long.

In 1927, the courts finally ruled in favor of Harriett Muse. The decision marked a turning point in the lives of George and Willie.

They were freed from the clutches of the circus and allowed to return to their family, who had never given up hope of their return.

Harriett Muse was known in her family as an iron-willed woman who protected her sons and battled for their return. (Photo courtesy of Nancy Saunders).

Eko and Iko’s Later Life

Life after the circus was not without its challenges. George and Willie had to reacquaint themselves with a world they had been separated from for over two decades. They faced curiosity and sometimes prejudice due to their unique appearance.

In 1928, the Muse brothers made a comeback to the circus world, initially under their own conditions.

Their performances took them to various places, from Buckingham Palace to the Hawaiian islands, where they shared the stage with sword swallowers, giants, and even some of the actors who would later appear as Munchkins in “The Wizard of Oz.”

As the late 1920s rolled in, they had risen to become top-billed sideshow attractions and prominent figures in the world of star performers, earning them prominent mentions in opening-day reports published by the New York Times from Madison Square Garden.

George and Willie Muse managed to send money back home to their mother from their earnings. With these wages, Harriett Muse purchased a small farm and gradually lifted herself out of poverty.

When she passed away in 1942, the sale of her farm provided the brothers with the means to move into a house in Roanoke, where they spent the remainder of their lives.

The Muses continued to work under somewhat improved conditions until their retirement in the mid-1950s.

George Muse passed away in 1972 due to heart failure, while Willie continued to live on until 2001, reaching the remarkable age of 108.

The brothers shown as Eko and Iko, sheepheaded cannibals from Ecuador.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Flickr / The Guardian / Washingtonian Magazine/ Truevine: Two Brothers, a Kidnapping, and a Mother’s Quest: A True Story of the Jim Crow South by Beth Macy).