Since its establishment in 1848, it has been important and influential in the history and culture of ethnic Chinese immigrants in North America. The area has a rich and complex history, marked by immigration, discrimination and resilience.

The first Chinese immigrants to San Francisco arrived during the California Gold Rush of 1848. They came seeking economic opportunity and to escape poverty and political instability in China.

Many of the early immigrants were men, and they worked in the mines, on the railroads, and in other manual labor jobs.

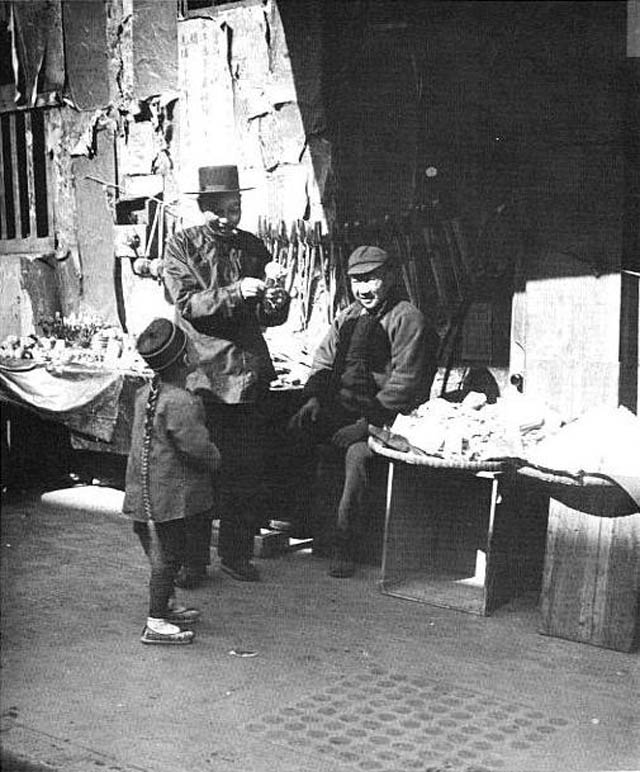

The toy peddler.

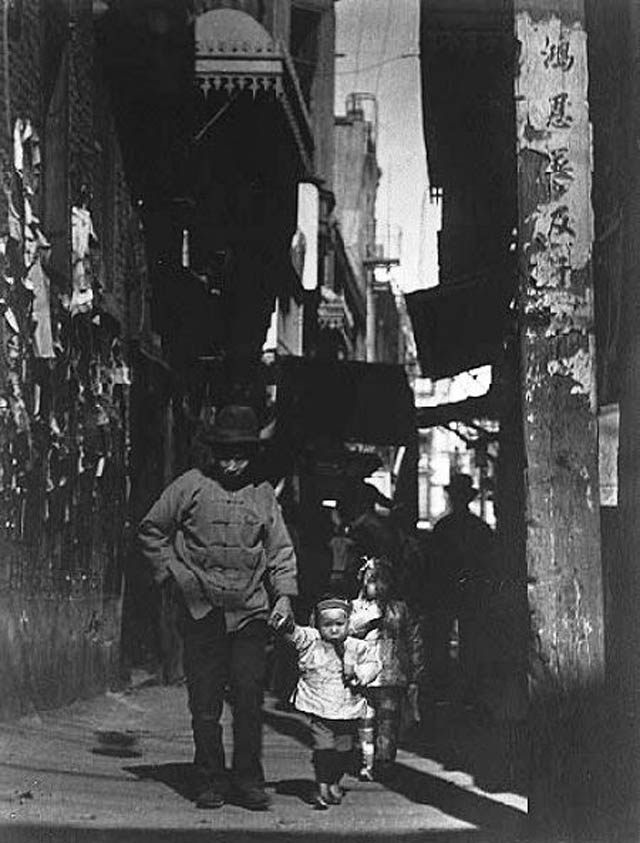

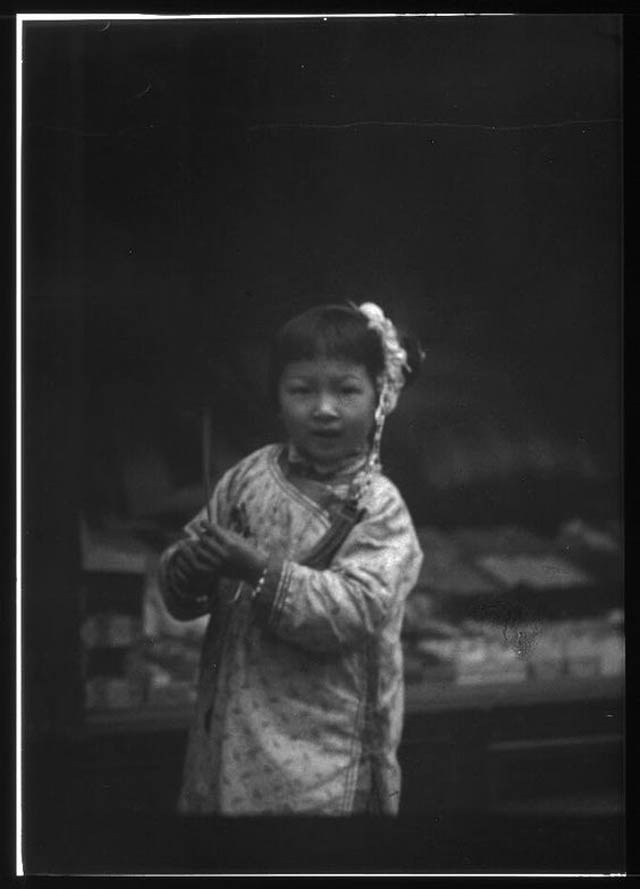

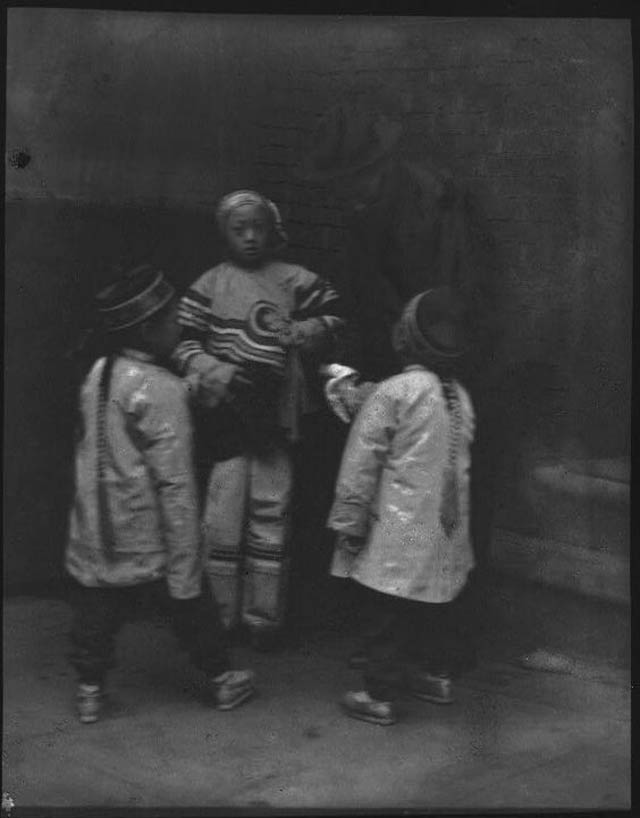

One of the earliest and most well-known depictions of San Francisco’s Chinatown comes from Arnold Genthe, a German-born photographer who arrived in the city in 1895.

Genthe was fascinated by the bustling streets and vibrant culture of Chinatown and spent many hours documenting the lives of its residents.

His photographs provide a rare glimpse into the daily routines and social customs of the community in the years leading up to the 1906 earthquake and fire that devastated the area.

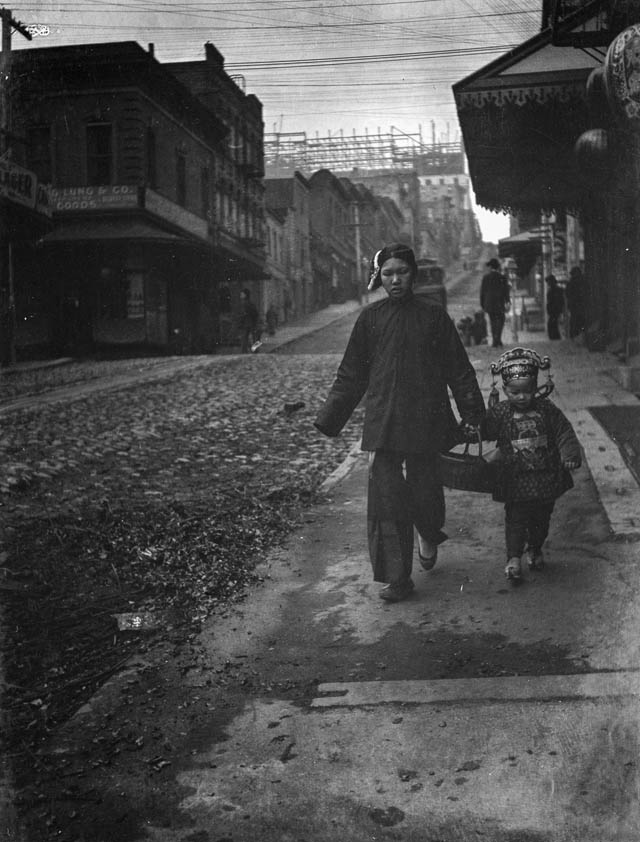

Genthe’s photographs capture the unique architecture of Chinatown’s narrow alleys, ornate buildings, and colorful storefronts. They also showcase the people who called this neighborhood home, from street vendors and laborers to families and community leaders.

Due to his subjects’ possible fear of his camera or their reluctance to have pictures taken, the photographer sometimes hid his camera.

He also sometimes removed evidence of Western culture from these pictures, cropping or erasing as needed. About 200 of his Chinatown pictures survive, and these comprise the only known photographic depictions of the area before the 1906 earthquake.

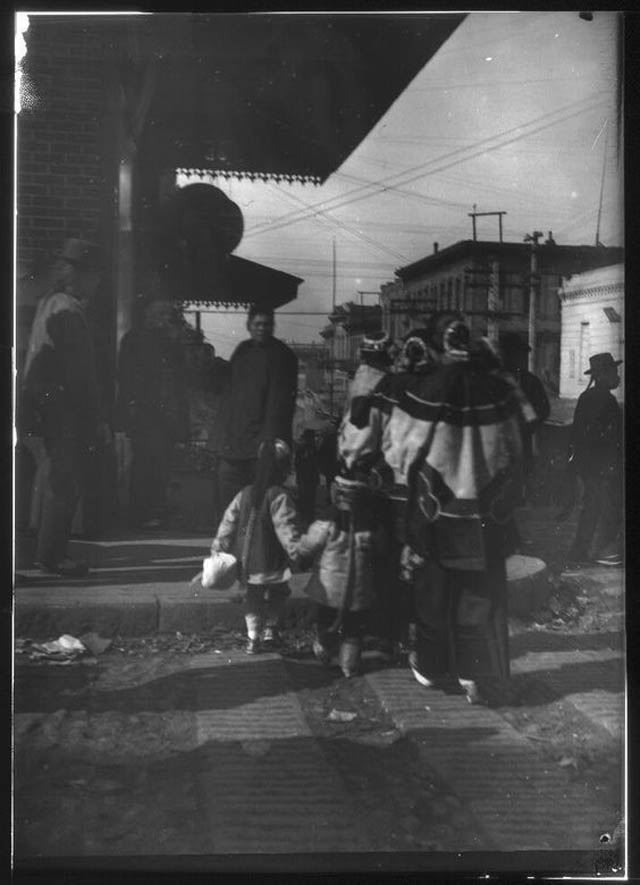

The Chinese Salvation Army, Chinatown, San Francisco 1896-1906.

In the mid-1840s, following defeat by Britain in the first Opium War, a series of natural catastrophes occurred across China resulting in famine, peasant uprisings and rebellions.

Understandably, when the news of gold and opportunity in far away Gum San, (Golden Mountain- the Chinese name for America) reached China, many Chinese seized the opportunity to seek their fortune.

The Chinese were met with ambiguous feelings by Californians. In 1850, San Francisco Mayor John W. Geary invited the “China Boys” to a ceremony to acknowledge their work ethic.

However, as the American economy weakened, the Chinese labor force became a threat to mainstream society. Racial discrimination and repressive legislation drove the Chinese from the gold mines to the sanctuary of the neighborhood that became known as Chinatown.

The only ethnic group in the history of the United States to have been specifically denied entrance into the country, the Chinese were prohibited by law to testify in court, to own property, to vote, to have families join them, to marry non-Chinese, and to work in institutional agencies.

The street of the gamblers (by day), Chinatown, San Francisco.

San Francisco’s Chinatown had twelve blocks of crowded wooden and brick houses, businesses, temples, family associations, and rooming houses for the bachelor majority, (in 1880 the ratio of men to women was 20 to 1) opium dens, gambling halls, and home to 22,000 people.

The atmosphere of early Chinatown was bustling and noisy with brightly colored lanterns, three-cornered yellow silk pennants denoting restaurants, calligraphy on signboards, flowing costumes, hair in queues, and the sound of Cantonese dialects.

In this familiar neighborhood, the immigrants found the security and solidarity to survive the racial and economic oppression of greater San Francisco.

The paper gatherer, Chinatown.

The San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906 was one of the most devastating natural disasters in American history, and its impact on the city’s Chinatown neighborhood was particularly significant.

At the time of the earthquake, Chinatown was a bustling and thriving neighborhood, home to over 22,000 residents and countless businesses and cultural institutions.

However, the earthquake and subsequent fire destroyed much of the area, displacing tens of thousands of residents and reshaping the neighborhood’s landscape and character for decades to come.

The earthquake, which struck on April 18, 1906, was centered in the vicinity of San Francisco, and its intensity was felt throughout the city.

In Chinatown, the damage was particularly severe, with many buildings collapsing and many more damaged beyond repair.

The resulting fires, which broke out in the aftermath of the earthquake, spread rapidly throughout the neighborhood, fueled by broken gas lines and high winds. By the time the fires were finally extinguished, over four days later, much of Chinatown had been reduced to ash and rubble.

Five girls in holiday finery, Chinatown, San Francisco 1896-1906.

Tens of thousands of residents were left homeless, with many forced to flee the city altogether. Business owners and merchants were similarly affected, with many losing their livelihoods and their life savings.

The neighborhood’s cultural institutions, including its temples, schools, and community centers, were also severely damaged or destroyed, leaving the community without many of the resources and institutions that had defined it for decades.

Despite the challenges, the Chinese community in San Francisco persevered, and they rebuilt Chinatown into a vibrant and thriving neighborhood.

Today, Chinatown is one of the most popular tourist destinations in San Francisco, and it is also a major center of Chinese culture in North America.

Woman and children walking down a street, Chinatown, San Francisco 1896-1906.

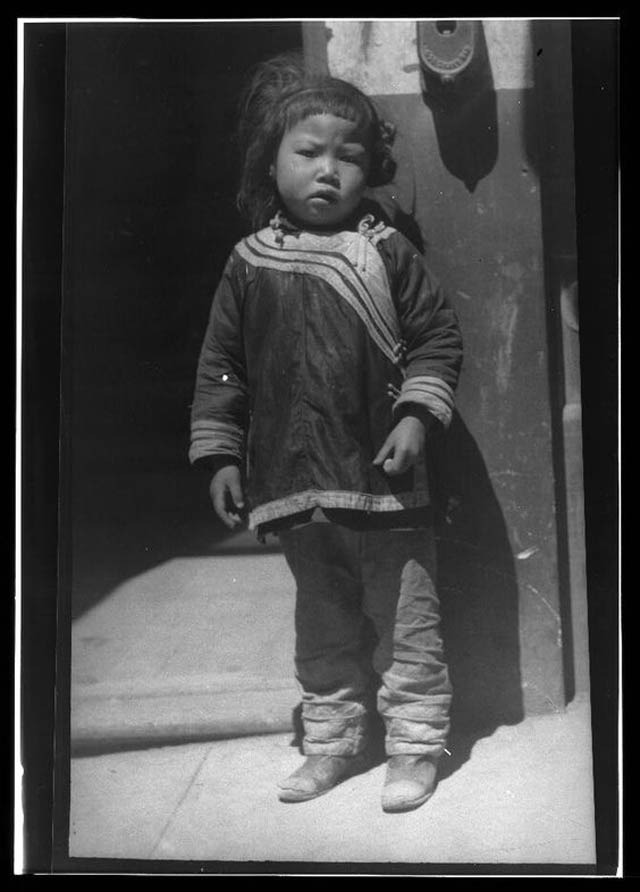

Little Plum Blossom, Chinatown, San Francisco 1896-1906.

In front of the Joss House, Chinatown, San Francisco 1896-1906.

A picnic on Portsmouth Square, Chinatown, San Francisco 1896-1906.

(Photo credit: Arnold Genther / Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons).