The Bathysphere was made of steel and was designed to withstand the tremendous pressure of the deep sea. It was equipped with several instruments, including cameras, thermometers, depth gauges, and a telephone that allowed communication with the surface.

The Bathysphere was lowered into the ocean using a cable and was used extensively in the 1930s to study the deep-sea environment.

Although it has since been replaced by newer submersibles, the Bathysphere’s contribution to oceanography and deep-sea exploration is significant.

Cross-sectional view of the Bathysphere.

In 1925, American naturalist William Beebe proposed the idea of a submersible vehicle that could take humans to the ocean depths. As of the late 1920s, the deepest humans could safely descend in diving helmets was several hundred feet.

Submarines of the time had descended to a maximum of 383 ft (117 m), but had no windows, making them useless for Beebe’s goal of observing deep-sea animals.

The deepest in the ocean that any human had descended at this point was 525 ft (160 m) wearing an armored suit, but these suits also made movement and observation extremely difficult.

What Beebe hoped to create was a deep-sea vessel which both could descend to a much greater depth than any human had descended thus far, and also would enable him to clearly observe and document the deep ocean’s wildlife.

William Beebe and Otis Barton with Bathysphere.

Beebe eventually teamed up with engineer Otis Barton, who had his own ambition to become a deep-sea explorer. Barton’s design called for a spherical vessel, as a sphere is the best possible shape for resisting high pressure.

The sphere had openings for three 3-inch-thick (76 mm) windows made of fused quartz, the strongest transparent material then available, as well as a 400-pound (180 kg) entrance hatch which was to be bolted down before a descent.

Initially, only two of the windows were mounted on the sphere, and a steel plug was mounted in place of the third window.

Oxygen was supplied from high-pressure cylinders carried inside the sphere, while pans of soda lime and calcium chloride were mounted inside the sphere’s walls to absorb exhaled CO2 and moisture.

Air was to be circulated past these trays by the Bathysphere’s occupants using palm-leaf fans. The design was originally called a “tank,” “bell,” or “sphere”. Beebe coined the name “bathysphere” using the prefix of the genus Bathytroctes.

A replica of the Bathysphere on display at the National Geographic museum in Washington DC.

The casting of the steel sphere was handled by Watson Stillman Hydraulic Machinery Company in Roselle, New Jersey, and the cord to raise and lower the sphere was provided by John A. Roebling’s Sons Company.

General Electric provided a lamp which would be mounted just inside one of the windows to illuminate animals outside the sphere, and Bell Laboratories provided a telephone system by which divers inside the sphere could communicate with the surface.

The cables for the telephone and to provide electricity for the lamp were sealed inside a rubber hose, which entered the body of the Bathysphere through a stuffing box.

After the initial version of the sphere had been cast in June 1929, it was discovered that it was too heavy to be lifted by the winch which would be used to lower it into the ocean, requiring Barton to have the sphere melted and recast.

The final, lighter design consisted of a hollow sphere of one-inch-thick (25 mm) cast steel which was 4.75 ft (1.45 m) in diameter.

Its weight was 2.25 tons above the water, although its buoyancy reduced this by 1.4 tons when it was submerged, and the 3,000 ft (910 m) of steel cable weighed an additional 1.35 tons.

On June 11, 1930, it reached a depth of 400 meters, or about 1,300 feet, and in 1934 Beebe and Barton reached 900 meters, or about 3,000 feet.

On June 11, 1930, it reached a depth of 400 meters, or about 1,300 feet, and in 1934 Beebe and Barton reached 900 meters, or about 3,000 feet.

Through these dives, the bathysphere proved its qualities but also revealed weaknesses. It was difficult to operate and involved considerable potential risks.

A break in the suspension cable would have meant certain death for the observers; surface waves and resulting movement of the boat could have produced such a fatal strain.

Beebe continued to conduct marine research for the rest of the 1930s, but after 1934 he felt that he had seen what he wanted to see using the Bathysphere, and that further dives were too expensive for whatever knowledge he gained from them to be worth the cost.

With the onset of World War II, Bermuda was transformed into a military base, destroying much of the natural environment and making further research there impractical.

After Beebe stopped using the Bathysphere, it remained the property of the New York Zoological Society. It remained in storage until the 1939 New York World’s Fair, where it was the centerpiece of the society’s exhibit.

After Beebe stopped using the Bathysphere, it remained the property of the New York Zoological Society. It remained in storage until the 1939 New York World’s Fair, where it was the centerpiece of the society’s exhibit.

During World War II, the sphere was loaned to the United States Navy, which used it to test the effects of underwater explosions.

The Bathysphere was next put on display at the New York Aquarium in Coney Island in 1957. In 1994, the Bathysphere was removed from the Aquarium for a renovation, and languished in a storage yard under the Coney Island Cyclone until 2005, when the Zoological Society (now known as the Wildlife Conservation Society) returned it to its display at the aquarium.

The Bermuda Aquarium, Museum and Zoo (to which Beebe had given some of Bostlemann’s original drawings) has long displayed a copy of the bathysphere, and another reproduction is on display at the National Geographic Museum.

William Beebe (left) and John T. Vann with Beebe’s bathysphere, 1934. (Photo by Britannica).

Although the technology of the Bathysphere was eventually rendered obsolete by more advanced diving vessels, Beebe and Barton’s Bathysphere represented the first time that researchers attempted to observe deep-sea animals in their native environment, setting a precedent which many others would follow.

Beebe’s Bathysphere’s dives also served as an inspiration for Jacques Piccard, the son of the balloonist Auguste Piccard, to perform his own record-setting descent in 1960 to a depth of seven miles (11 km) using a self-powered submersible called a bathyscaphe. The Bathysphere itself served as a model for later submersibles such as the DSV Alvin.

William Beebe (center) with his bathysphere, 1932. (Photo by Britannica).

Beebe named several new species of deep-sea animals on the basis of observations he made during his Bathysphere dives, initiating a controversy which has never been completely resolved.

The naming of a new species ordinarily requires obtaining and analyzing a type specimen, something which was obviously impossible from inside the Bathysphere.

Some of Beebe’s critics claimed that these fish were illusions resulting from condensation on the Bathysphere’s window, or even that Beebe willfully made them up, although the latter would have been strongly at odds with Beebe’s reputation as an honest and rigorous scientist.

Barton, who was resentful that newspaper articles about his and Beebe’s Bathysphere dives often failed to mention him, added to ichthyologists’ skepticism by writing letters to newspapers that contained wildly inaccurate accounts of their observations.

While many of Beebe’s observations from the Bathysphere have since been confirmed by advances in undersea photography, it is unclear whether others fit the description of any known sea animal.

One possibility is that although the animals described by Beebe indeed exist, so much remains to be discovered about life in the deep ocean that these animals have yet to be seen by anyone other than him.

Bathysphere being raised above the surface. (Photo by New York Public Library).

Bathysphere being lowered into the ocean, 1932. (Photo from Wildlife Conservation Society).

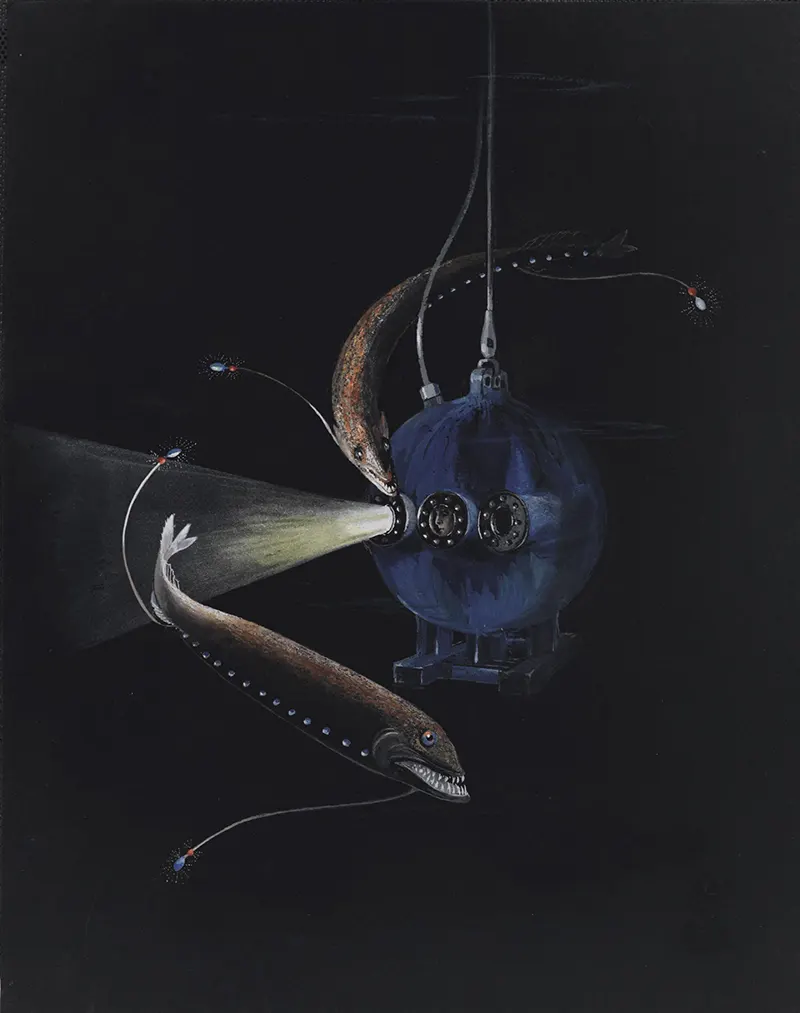

Else Bostelmann’s illustration of the Bathysphere’s descent, painted for the National Geographic article which Beebe wrote in return for the National Geographic Society sponsoring his dives.

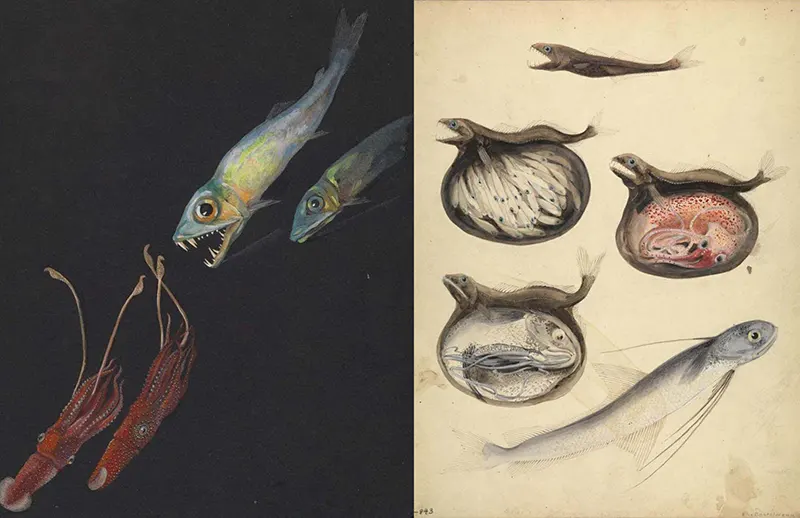

Deep sea life illustrations by Else Bostelmann.

Bathysphere Entrance Port. (Photo by Scott Hanko).

Bathysphere Viewing Ports. (Photo by Scott Hanko).

(Photo credit: Wildlife Conservation Society Archives / Wikimedia Commons / The Official William Beebe Web Site).