Before the advent of the washing machine, laundry was often done in a communal setting. Villages across Europe that could afford it built a washhouse, sometimes known by the French name of lavoir.

Water was channeled from a stream or spring and fed into a building, possibly just a roof with no walls. This washhouse usually contained two basins – one for washing and the other for rinsing – through which the water was constantly flowing, as well as a stone lip inclined towards the water against which the wet laundry could be beaten.

The job of doing the laundry was reserved for women, who washed all their family’s laundry. Washerwomen (laundresses) took in the laundry of others, charging by the piece.

As such, washhouses were an obligatory stop in many women’s weekly lives and became a sort of institution or meeting place. It was a women-only space where they could discuss issues or simply chat.

Washhouse in Sanremo, Italy, at about the turn of the 20th century.

Sometimes large metal cauldrons (a “wash copper”, even when not made of that metal), were filled with fresh water and heated over a fire, as hot or boiling water is more effective than cold in removing dirt. A posser could be used to agitate clothes in a tub.

An early example of washing by machine is the practice of fulling. In a fulling mill, the cloth was beaten with wooden hammers, known as fulling stocks or fulling hammers.

The first English patent under the category of washing machines was issued in 1691. A drawing of an early washing machine appeared in the January 1752 issue of The Gentleman’s Magazine, a British publication.

Jacob Christian Schäffer’s washing machine design was published in 1767 in Germany. In 1782, Henry Sidgier issued a British patent for a rotating drum washer, and in the 1790s, Edward Beetham sold numerous “patent washing mills” in England.

One of the first innovations in washing machine technology was the use of enclosed containers or basins that had grooves, fingers, or paddles to help with the scrubbing and rubbing of the clothes.

The person using the washer would use a stick to press and rotate the clothes along the textured sides of the basin or container, agitating the clothes to remove dirt and mud.

Model Steam Laundry, Colfax, Washington, circa 1900.

The Industrial Revolution completely transformed laundry technology. Christina Hardyment, in her history from the Great Exhibition of 1851, argues that it was the development of domestic machinery that led to women’s liberation.

The mangle (or “wringer” in American English) was developed in the 19th century — two long rollers in a frame and a crank to revolve them.

A laundry worker took sopping wet clothing and cranked it through the mangle, compressing the cloth and expelling the excess water.

The mangle was much quicker than hand twisting. It was a variation on the box mangle used primarily for pressing and smoothing cloth.

Southern Ohio family in front of new washing machine, 1911.

Meanwhile, 19th-century inventors further mechanized the laundry process with various hand-operated washing machines to replace tedious hand rubbing against a washboard.

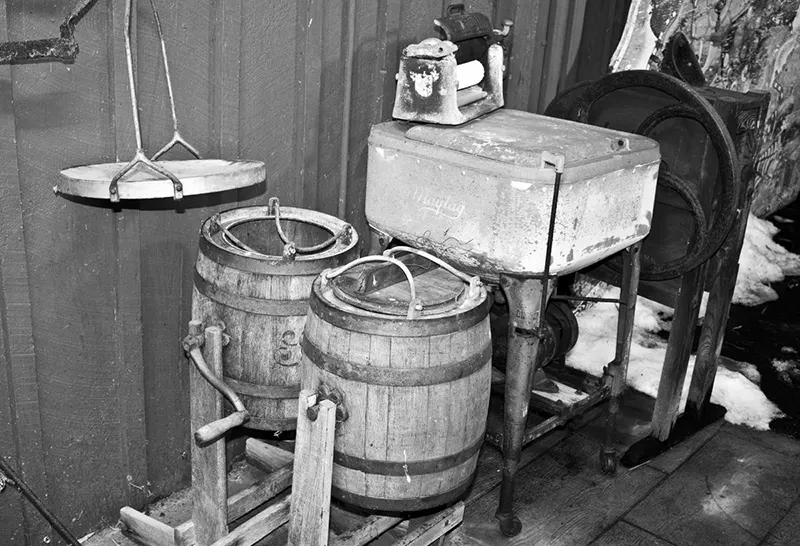

Most involved turning a handle to move paddles inside a tub. Then some early-20th-century machines used an electrically powered agitator. Many of these washing machines were simply a tub on legs, with a hand-operated mangle on top.

The Thor washing machine was the first electric clothes washer sold commercially in the United States. Produced by the Chicago-based Hurley Electric Laundry Equipment Company, the 1907 Thor is believed to be the first electrically powered washer ever manufactured, crediting Hurley as the inventor of the first automatic washing machine.

Designed by Hurley engineer Alva J. Fisher, a patent for the new electric Thor was issued on August 9, 1910, three years after its initial invention.

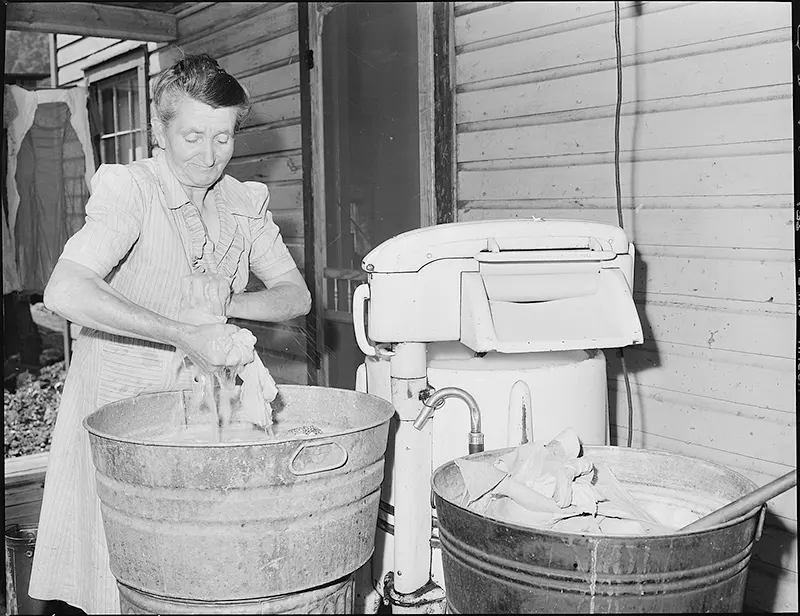

Wife of miner on washday. Southern Coal Corporation, Bradshaw Mine, Bradshaw, McDowell County, West Virginia. 1946.

US electric washing machine sales reached 913,000 units in 1928. However, high unemployment rates in the Depression years reduced sales; by 1932 the number of units shipped was down to about 600,000.

Washer design improved during the 1930s. The mechanism was now enclosed within a cabinet, and more attention was paid to electrical and mechanical safety. Spin dryers were introduced to replace the dangerous power mangle/wringers of the day.

By 1940, 60% of the 25,000,000 wired homes in the United States had an electric washing machine. Many of these machines featured a power wringer, although built-in spin dryers were not uncommon.

A large number of US manufacturers introduced competing for automatic machines (mainly of the top-loading type) in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

A large number of US manufacturers introduced competing for automatic machines (mainly of the top-loading type) in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

General Electric also introduced its first top-loading automatic model in 1947. This machine had many of the features that are incorporated into modern machines.

Another early form of automatic washing machine manufactured by The Hoover Company used cartridges to program different wash cycles.

This system, called the “Keymatic”, used plastic cartridges with key-like slots and ridges around the edges. The cartridge was inserted into a slot on the machine and a mechanical reader operated the machine accordingly.

Several manufacturers produced semi-automatic machines, requiring the user to intervene at one or two points in the wash cycle.

A common semi-automatic type (available from Hoover in the UK until at least the 1970s) included two tubs: one with an agitator or impeller for washing, plus another smaller tub for water extraction or centrifugal rinsing.

In the UK and most of Europe, electric washing machines did not become popular until the 1950s. This was largely because of the economic impact of World War II on the consumer market, which did not properly recover until the late 1950s.

In the UK and most of Europe, electric washing machines did not become popular until the 1950s. This was largely because of the economic impact of World War II on the consumer market, which did not properly recover until the late 1950s.

The early electric washers were single-tub, wringer-type machines, as fully automatic washing machines, were extremely expensive.

During the 1960s, twin tub machines briefly became very popular, helped by the low price of the Rolls Razor washers. Twin tub washing machines have two tubs, one larger than the other.

The smaller tub in reality is a spinning drum for centrifugal drying while the larger tub only has an agitator in its bottom.

Some machines could pump used wash water into a separate tub for temporary storage and to later pump it back for re-use.

September 1938. “Farm wife washing clothes. Lake Dick Project, Arkansas.”

A 1766 illustration of Schäffer’s washing machine.

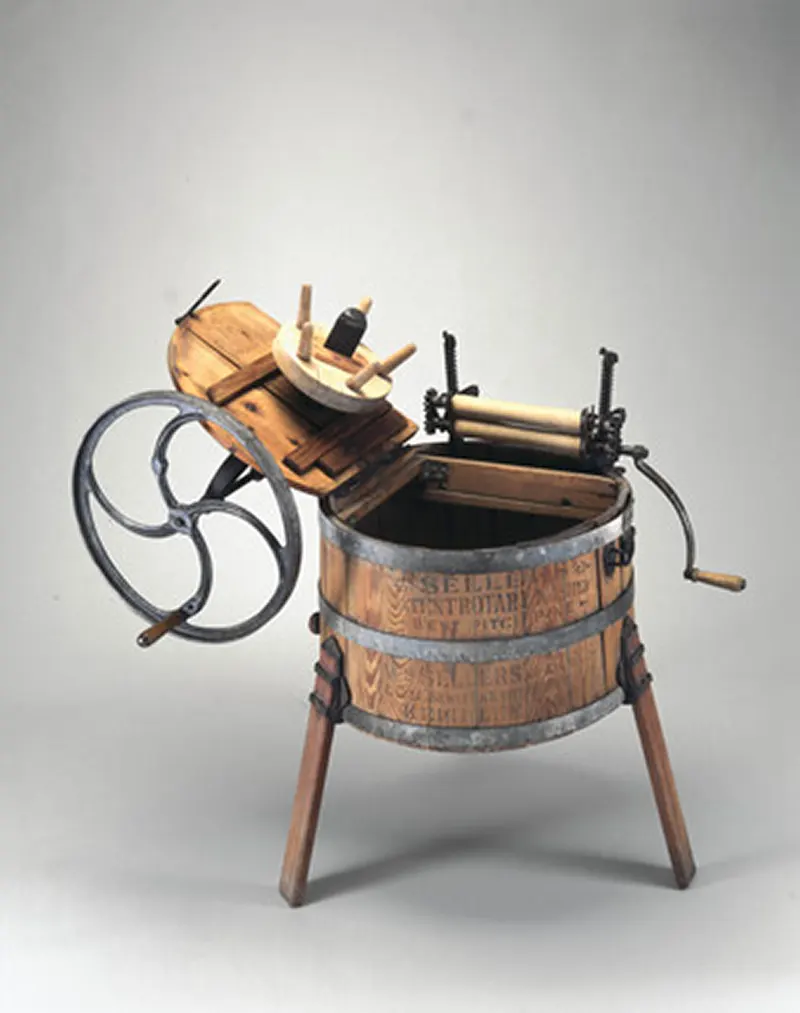

A simple, crank-operated washing machine.

A 1923 electric Miele washing machine with a built-in mangle.

“Woman’s Friend” machine (c. 1890).

The Rotary Machine, 1858.

Thor Electric Washing Machine, 1935.

Maytag Wringer Washer, 1940.

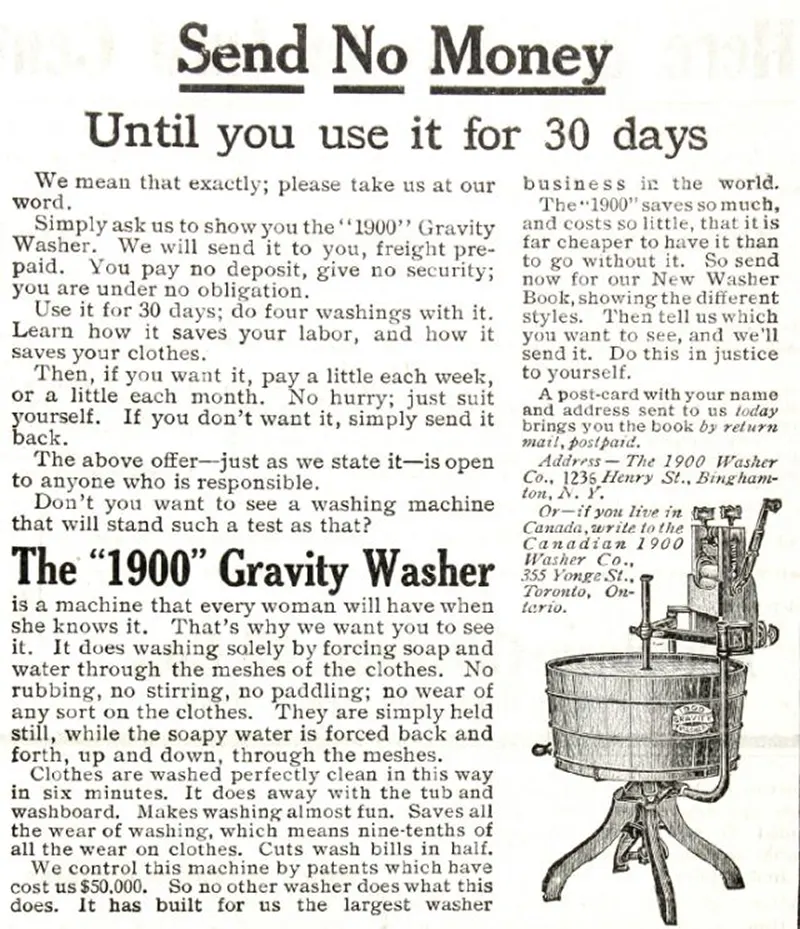

Gravity Washer, 1900/

Washing Machine, 1890.

Washing Machine, 1928.

This state-of-the-art washing machine boasted that a woman could do a load in six minutes by simply sitting and turning the crank handle. To encourage sales, mail-order catalogs allowed potential buyers to order one at no cost and test it in their homes for a month.

1916 vintage advertising illustration for Maytag Washing Machine.

Kentucky Utilities Company, woman demonstrating wringer-type washing machine, 1943.

Ben Leeson and his wife, circa 1901.

“Farm Woman using her electric mangle”. Montgomery County, Indiana, 1930.

Actress Eileen Pollock is pictured with an electric washing machine at the 1935 Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition at Olympia.

(Photo credit: Shorpy / Wikimedia Commons / Flickr / Pinterest / Library of Congress).